DISCLOSURE: This post may contain affiliate links, meaning I get a commission if you decide to make a purchase through my links, at no cost to you. Please read my disclosure for more info.

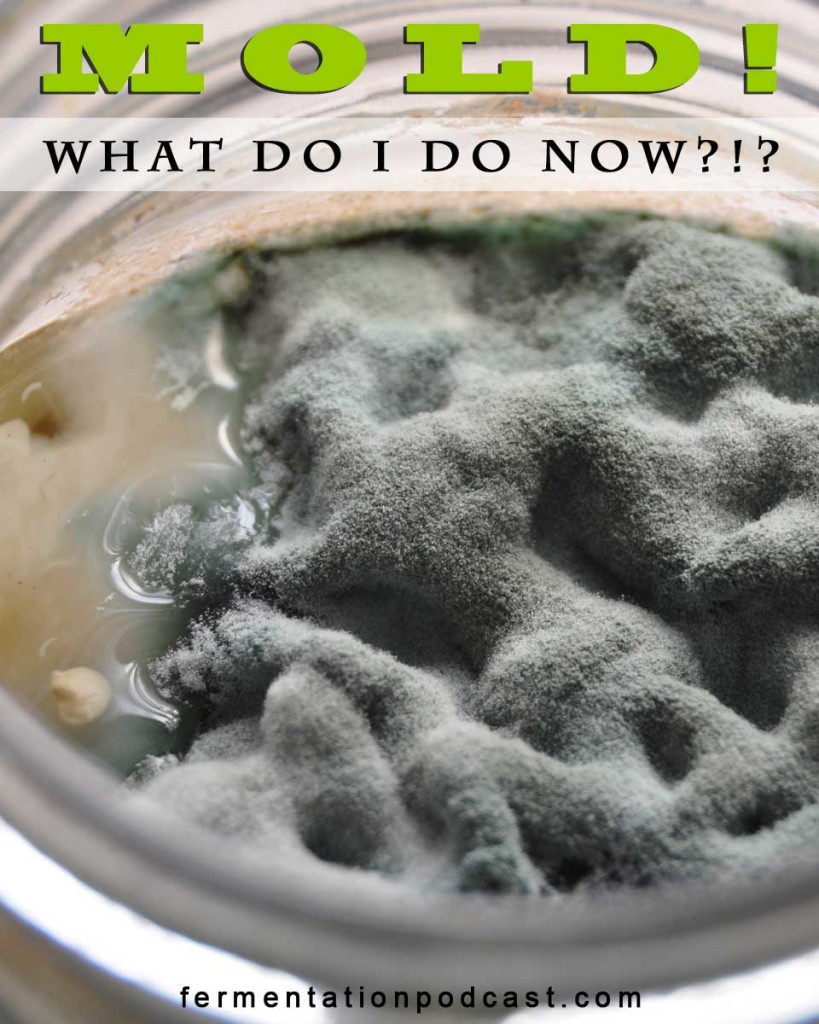

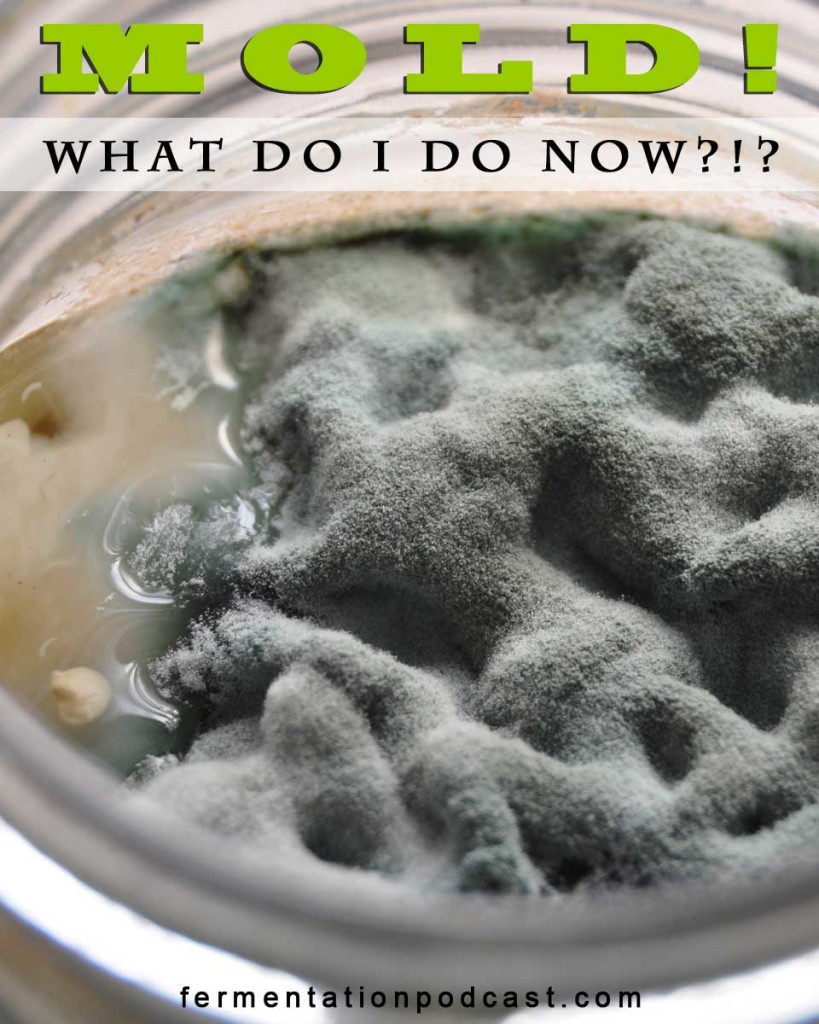

Occasionally I’ll make a ferment, let it develop over a few days or so, pop it in the fridge, and then weeks or months later it’s possible I might see the often-dreaded MOLD on top of my ferment. What do I do?

This is a followup to Mold in My Pickled Peppers and I also go over this in Episode 11 – Listener Feedback, Cashew Cheese, Mold, & Food Safety. Have a listen!

I get questions on mold and food safety like this often:

- What is mold and why is there mold on top of my sauerkraut, pickles, etc.?

- Is it harmful or dangerous to eat mold and what can it do to you?

- Is it safe to scrape mold off the surface of a brine and then eat the ferment that is below the brine level?

- Aren’t you afraid of mycotoxins and doesn’t mold have roots?

- How can I prevent mold from growing on my ferments and what do I do now that I have it?

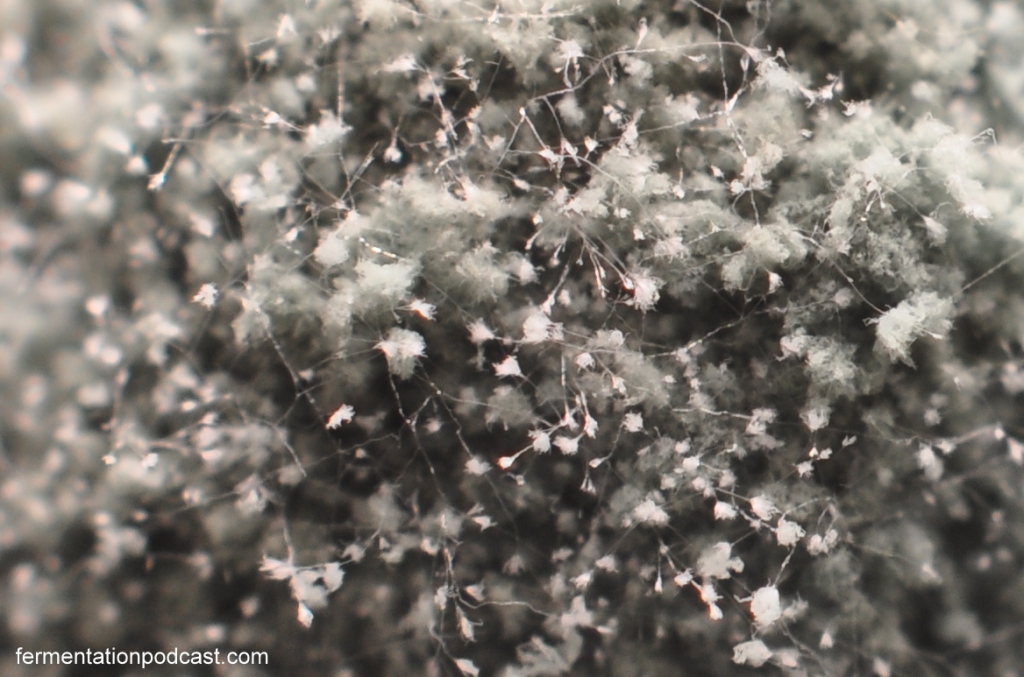

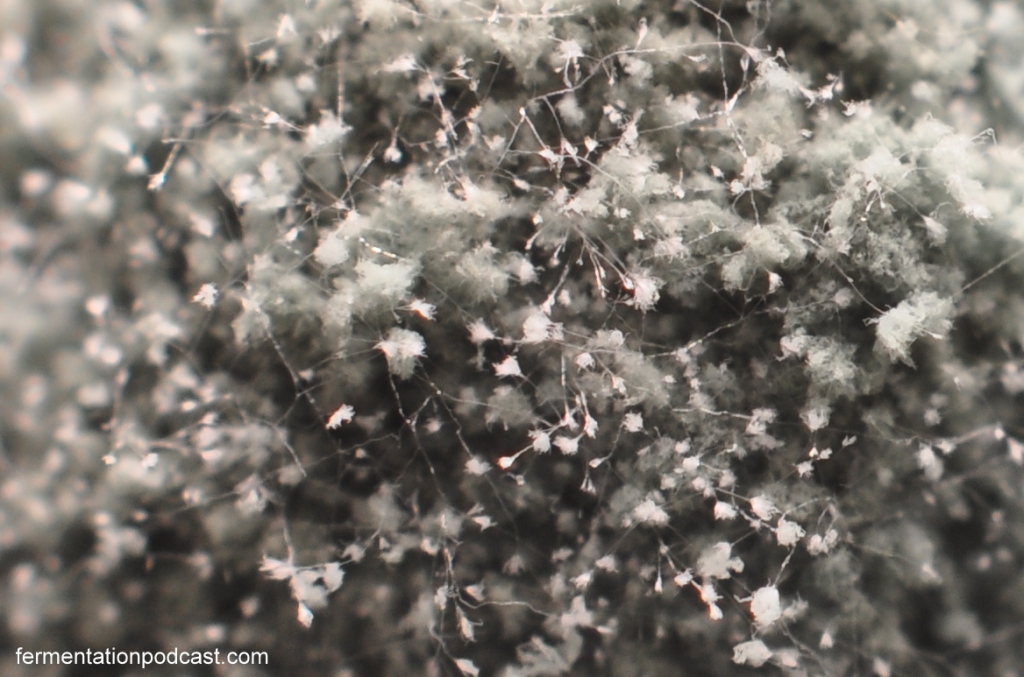

I’ll go over each of these questions one by one and add some pictures to so you can see mold up close and personal. I had one person comment on some of these up close pictures of mold and an interesting thought came to mind that when seen up close, mold is strangely beautiful. I’d have to say that I agree.

1. What is mold and why is there mold on top of my sauerkraut, pickles, etc.?

Mold is a fungus organism that grows in filaments that are connected, so it’s a thread-like type of creature that’s multi-celled in contrast to bacteria which is a single-celled organism. The USDA to their credit has a good article about Molds on Food, however they actually don’t cover fermented foods at all and have no comment on surface molds on top of brines.

Mold grows from mold spores that are present everywhere in the air and begin growing when they land on a wet surface that has nutrients (such as your food). They can actually survive in acidic foods so it’s not necessarily the acidity that deters them. Mold spores range in size anywhere between 3-40 microns which is the same size or slightly larger than the size of a red blood cell. The size is important because the naked human eye can see down to 40 microns so only the largest sizes of mold could possibly be seen unaided.

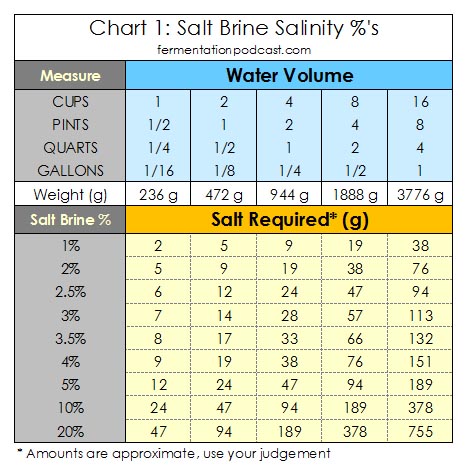

Engineering Toolbox, Wikipedia, and just a general search on Google yields great lists of particle sizes in microns of different things to give you a good comparisons. These range widely but I’ll put an average in the chart below. Here’s a small sample of sizes of particles for reference in relation to mold spores:

| Particle |

Size

(microns) |

| One Inch |

25400 |

| Eye of a needle |

1230 |

| Mist (water) |

70 – 350 |

| Human Hair |

17 – 180 |

| Pollen |

60 |

| Mold Spores |

3 – 40 |

| Red Blood Cells |

5 – 10 |

| Spider Web |

2 – 3 |

NOTE – The human eye is said to have a limit to see down to 40 microns.

There is no reasonable way to eliminate mold spores when it comes to removing them from a human environment so you’re always going to be in the presence of them. They only become a problem when they begin to multiply.

The first question you want to ask though is, do you really have mold or is it harmless kahm yeast?

Kahm yeast is a harmless surface yeast that grows on ferments that haven’t reached a high enough acidity. It’s usually white in color and is almost like a film on the surface. Kahm yeast isn’t dangerous, but it can give your ferment an off flavor so you should remove it to make sure your ferment tastes its freshest.

If the stuff growing on your ferment is darker in color or furry then you most likely have mold.

Contributing factors for mold growing on ferments:

- Keep it below the brine level – vegetables aren’t submerged in their anaerobic environment and are now in an aerobic oxygen environment that mold likes. Using glass fermentation weights or fermentation lids with air locks helps

- Starting with rotten vegetables – vegetables that are starting to go bad have a higher mold content than fresh vegetables which gives the mold a starting advantage on the other bacteria and yeasts which are competing in the same space

- Warmer temperatures – the room temperature warms up past the cooler temperatures desired by vegetable ferments warmer than 65-70 degrees

- Salt – not having enough salt can have a contributing factor

- Chemicals or pesticides – using water that has chlorine or vegetables that have pesticides could possibly interfere with the fermentation process

2. Is it harmful or dangerous to eat mold and what can it do to you?

Mold is not something you want to mess around with when it comes to food, but there are also molds that people grow on purpose such as those as you would think of with cheeses like blue cheese.

If you have a piece of food like bread sitting on the counter too long, assuming that it doesn’t contain many preservatives, it will probably start to develop a mold growth. Just like in the ground, once you start to see mold or the fruiting bodies of mold developing on the surface, the mold is well underway in the crevices of that piece of food and is probably already all throughout it.

For food in an aerobic environment it’s probably always the case that these should be thrown away because of the health consequences that it can have on you.

Molds have three methods in which can make people sick and eating mold can have any of these side effects:

- Infection of the person – this is an actual infection of the mold onto the person such as athlete’s foot, and also is much more uncommon unless a person has a severely reduced immune system.

- Allergic reaction – this is where a person is allergic to the actual mold or mold spores (which is either inhaled or absorbed through the skin).

- Chemical toxicity (mycotoxins) – these are the chemicals or small molecules of toxins formed by the hyphae of molds (the filaments that connect them) that can have severe chronic and acute health effects on your body. These are sometimes inhaled but more often usually consumed through food.

There are people who accidentally eaten mold such as a piece of bread that was moldy and haven’t gotten sick. Most likely the extreme pH of the human stomach at 1.5 to 3.5 probably destroyed the small amount that would have done them harm, or they could have gotten lucky with a type that wouldn’t have gotten them sick. The CDC says that there could be anywhere between tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of different types of fungi.

Dealing with the effects of mold on your body can take quite a long time to get over so if you have any food that has mold on it in an aerobic environment, my advice is to throw it away and not consume it.

When dealing with food that is in an anaerobic environment, that might be a slightly different story as I’ll explain below, but everyone should come to their own conclusions and be responsible for their own actions.

3. Is it safe to scrape mold off the surface of a brine and then eat the ferment that is below the brine level?

When going through this question, I can only answer for myself as to what I do and I’m not advising anyone to consume a ferment that has mold. There are people that have severe allergic reaction to molds, mold spores, or the toxins (mycotoxins) that the mold filaments produce, so each person has to decide what’s appropriate for them.

However, much more research and factual evidence including pictures and data on a microscopic level needs to be done in this area as there is too much conflicting advice, hearsay, and not enough science to put this to rest.

Here are some thoughts that I follow myself though:

- As far as anecdotal advice that seems to hold up, in Sandor Katz’s book The Art of Fermentation and Wild Fermentation, he specifically says that if you have a ferment in a brine and the vegetable matter is below the brine, you can safely scrape the mold off the surface of the brine and consume the ferment.

- He also says that if you have pieces that have gone above the brine level and have molded, simply cut those off, thrown them away, and the rest below the brine level is fine.

- I feel (for myself) that if a brined ferment has a little mold, I’ve scraped the mold off the surface, cut off molded pieces or toss them entirely, and the ferment underneath the brine has been fine for consumption and I’ve have never had a problem as well as I’ve heard the same from many others.

- There have been occasions, such as the pictures on this page, where there has been a substantial amount of mold covering the surface, so I tossed everything out and started over. Like I’ve said before, there’s always the next batch.

4. Aren’t you afraid of mycotoxins and doesn’t mold have roots?

In terms of mycotoxins, I have never had any adverse reactions to simple vegetable ferments and I am not worried about this in the slightest.

Often you’ll hear the argument, “But mold has roots which means it’s deep into the entire batch so the whole batch should be thrown out.”

When you look on the surface of a growing mold, there’s an enormous amount of fruiting bodies that create the mold spores that then cause the mold to spread through the air. At the same time, if you magnify it enough, you can see the filaments of the hyphae that connect the mold cells together which helps mold spread over a surface.

I’ve gotten macro photographs of mold up close and personal and I mean within 1 mm from the lens where I couldn’t get any closer than that unless I got a microscope and when I’ve looked under a mass of mold, I haven’t seen these roots myself. I expect not to be able to see them with my naked eye since it’s beyond the eye’s capability, but with my camera gear I expect to see them and I haven’t.

I’ve seen young mold that starts to grow and some of the filaments are below the brine surface, but as the mold gets older, those filaments are no longer visible and possibly die off.

I took the older mold, carefully flipped it over, and it looks like a solid mass with no roots in the actual brine.

(For reference, that slightly tannish-brown object on the right is a jalepeno pepper seed)

I think more people need to get involved in this research and either solve this once and for all or point to actual credible scientific evidence with pictures – and when I mean evidence, I’m talking about evidence of roots of mold growing down from the aerobic surface of a brine into the anaerobic brine, which I’m not convinced that it does.

From my experience in permaculture, the fermentation process locks up harmful toxins in the environment, which is natures way of cleaning things up. This is seen in a compost pile where toxic chemicals are either

- broken down into less toxic substances

- or locked up in the carbon of plants from the fermentation process rendering them inert

It’s possible that the anaerobic process of lacto-fermentation deactivates or locks up these toxins in mycotoxins. I think this would make a great science fair project for a student and encourage some experimentation

5. How can I prevent mold from growing on my ferments and what do I do now that I have it?

The best way to deal with mold is probably not to encourage it in the first place and you can do that by making it less hospitable for mold to grow.

Some ideas on this include:

- Create an anaerobic environment – keep the oxygen out of the container by using any of the following:

- the time-tested method of a fermentation crock with a water moat which burps out CO2 and prevents oxygen from entering the fermentation vessel (like a ceramic crock)

- a mason jar with an air lock or fermentation lid (or something like a Pickl-It)

- or just trying as much as possible to keep the brine surface as small as possible (like putting a jelly jar inside of a larger wide mouth jar

- Use fresher vegetables – rotten vegetables are already going to have a higher mold content

- Ferment in slightly colder temperatures – find a cool place in your house, for people in a cooler environment use your root cellar, create a temperature controlled container like a cooler with cold water, etc.

- Use more salt – it might give your ferment a slight edge with a bit more salt, try it and see

If you already have a mold infestation, you have a few options and these are highly personal so decide for yourself:

- Use the old adage “When in doubt, throw it out” which is perfectly acceptable! Just try again.

- Skim the mold off the top and don’t worry about it

- Skim the mold off the top and try and create a more anaerobic environment for your ferment, and ferment a little longer

That’s really it. If you’re tossing the whole batch and want to make sure to get rid of the mold that might still stick around the dry parts of your container, scrub with soapy water, vinegar, and if you need like Mark Campbell suggests with ceramic crock weights, put them in the oven on very low for a while to “cook” the mold to destroy it.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this post and if you do happen to get some mold in your ferments, don’t feel bad! It happens to all of us and it’s just part of life’s natural processes. Mold plays a very important part in nature and I’d rather have food that can grow mold on it rather than having food that could sit on the counter for years and look just as fresh as when you first buy it.

Leave me some comments and happy fermenting!